Barking & Dagenham is the only borough in the capital to claim access to a freeport zone – a specially designated economic area where normal tax and customs rules do not apply.

But what does freeport status mean for a borough currently up against an undersupply of housing? How have they worked in the past and what other factors will support regeneration and new housing development in the area?

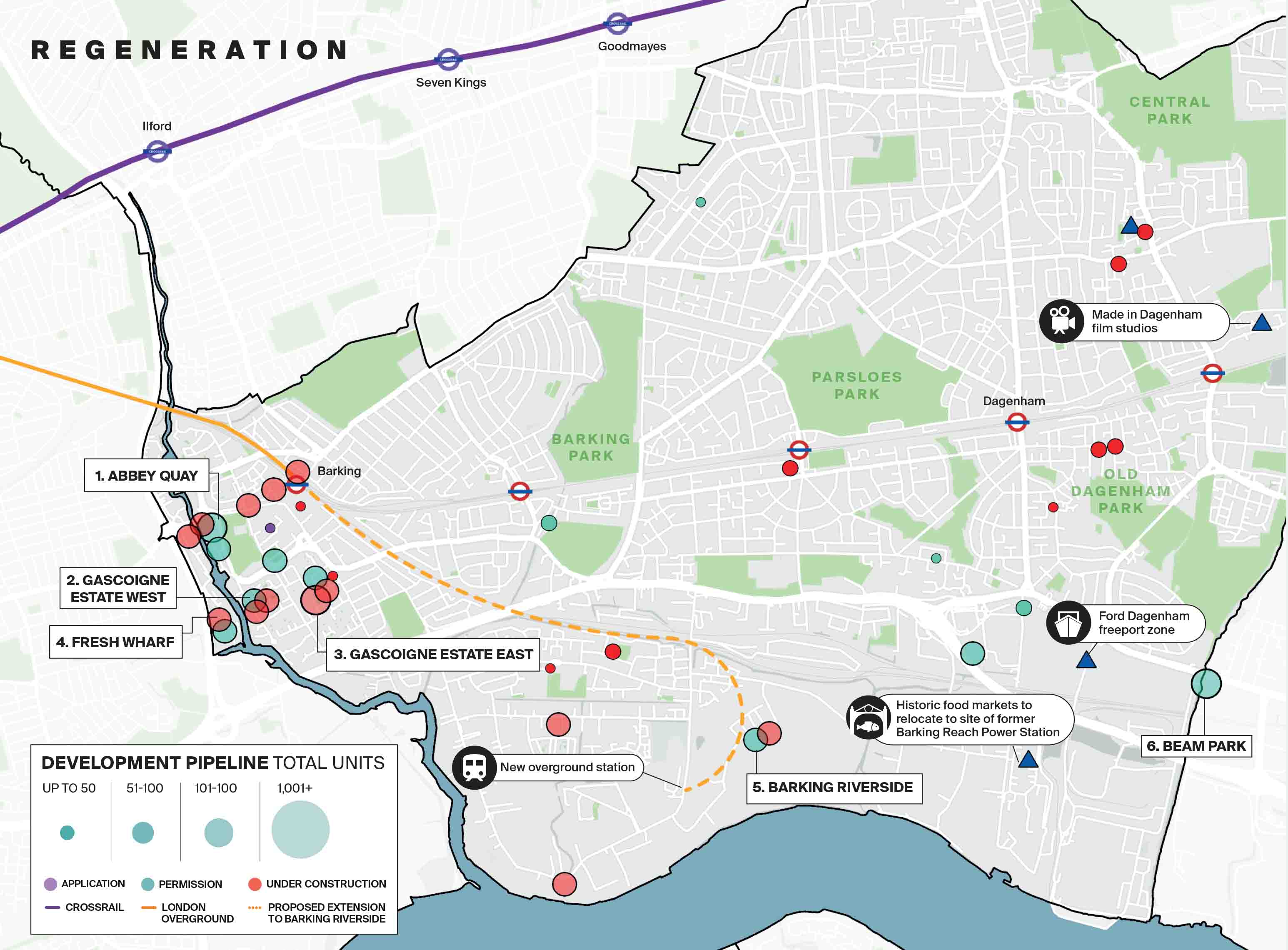

Firstly, it’s worth noting that for Barking this is part of a wider regeneration picture. A new Knight Frank report on the area explores how new film studios in Dagenham combined with the imminent arrival of historic City of London markets, the Elizabeth Line and the Overground extension to Barking Riverside will transform the east London borough.

The freeport alone is expected to create an additional 25,000 jobs in the area, along with the regeneration of 1,700 acres for commercial use, having been given the green light in the spring Budget.

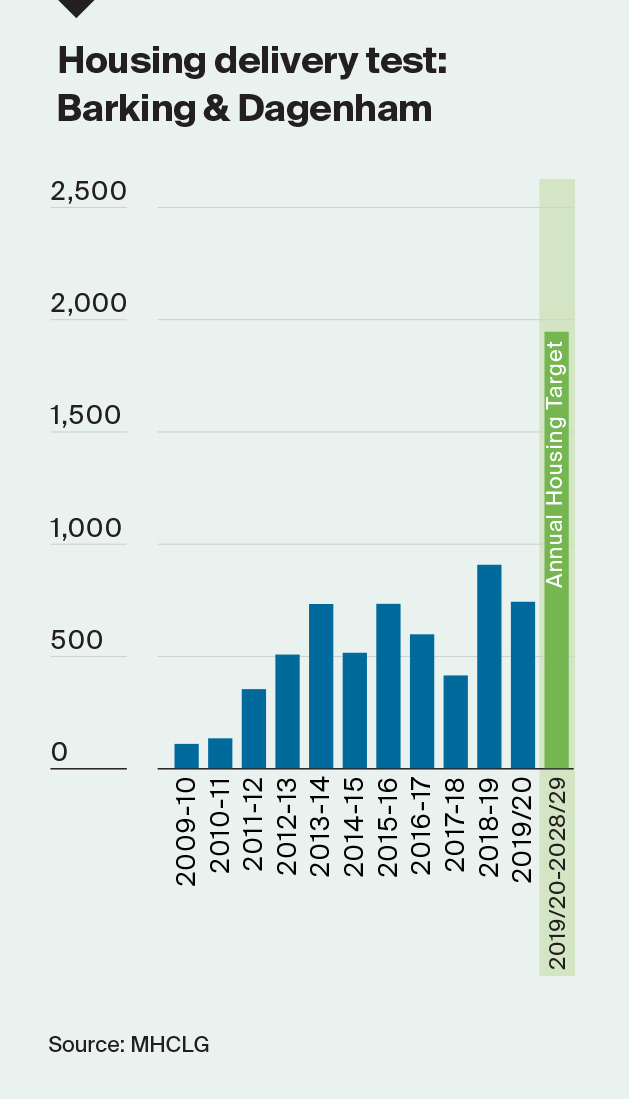

Job creation and new infrastructure are supporting much needed new housing development. There are around 13,500 units in the development pipeline in Barking, according to Molior, which will be delivered over the coming years. The London Plan suggests the borough will require 1,944 homes every year for a decade to meet its housing need.

The borough has not kept pace with housing need in recent years: according to the results of the 2020 Housing Delivery Test – which measures housing delivery against housing need over the past three years – Barking & Dagenham built 57% of the homes required, one of only eight London boroughs which delivered under 75% of the required amount. As a result, planning policy in the borough will become subject to the “presumption in favour of sustainable development”.

How will the new Dagenham freeport work?

The Thames Freeport bid will link the ports of Tilbury and London Gateway, in Essex, with Ford’s Dagenham engine plant further west.

The bid – by DP World, Forth Ports and Ford – will now work HM Treasury and HMRC to ‘review and confirm’ the boundaries of their proposed tax sites. The Budget paper suggests that it may take over a year for the freeport tax sites to be designated.

The other seven selected sites are outside London in places including Plymouth, Teeside and Liverpool. The UK previously had seven freeports between 1984 and 2012. Locations included Liverpool and Southampton.

According to the Institute for Government, freeports are similar to free zones, or ‘enterprise zones’, which are designated areas subject to a broad array of special regulatory requirements, tax breaks and government support. There are currently 48 of those across England.

So goods that arrive into freeports from abroad are not subject to tariffs. Tax breaks include full stamp duty land tax relief on the purchase of land and buildings within the freeport zone where properties are used for a qualifying commercial activity.

But the critical difference, the Institute says, is that a freeport aims to “specifically encourage businesses that import, process and then re-export goods, rather than more general business support or regeneration objectives.”

Read the original post here.